Tron: Ares is a good movie (and we don't need more Tron movies)

So I saw Tron: Ares and I didn’t hate it.

Oop, sorry, that was heresy and I’m being banished to the Game Grid now.

I’m sure this surprises nobody, as I’m kind of in the key demographic for this movie. But it’s worth noting that more importantly, I think I liked it better than Tron: Legacy. It may have told a better story for its era. Because that’s the hard thing about this franchise: there are 43 years between the first movie and this one; nearly half a century.

The original Tron has a special place in my heart (I’m about as old as it), but I think it can’t be remade for some very specific reasons. And I think Tron: Ares May be the better film of the two new ones for not trying to remake it. To really unbox where I’m going with this, I’m going to have to walk through all three movies and one game. Spoilers for all of this:

- Tron

- Tron 2.0

- Tron: Legacy

- Tron: Ares

We’re going to take a long walk and talk about the difference between setting and story, tropes and tools, and maybe about why we don’t need to keep making Tron movies.

So, let’s enter the first grid.

Flynn is Alice

The rabbit hole is a laser

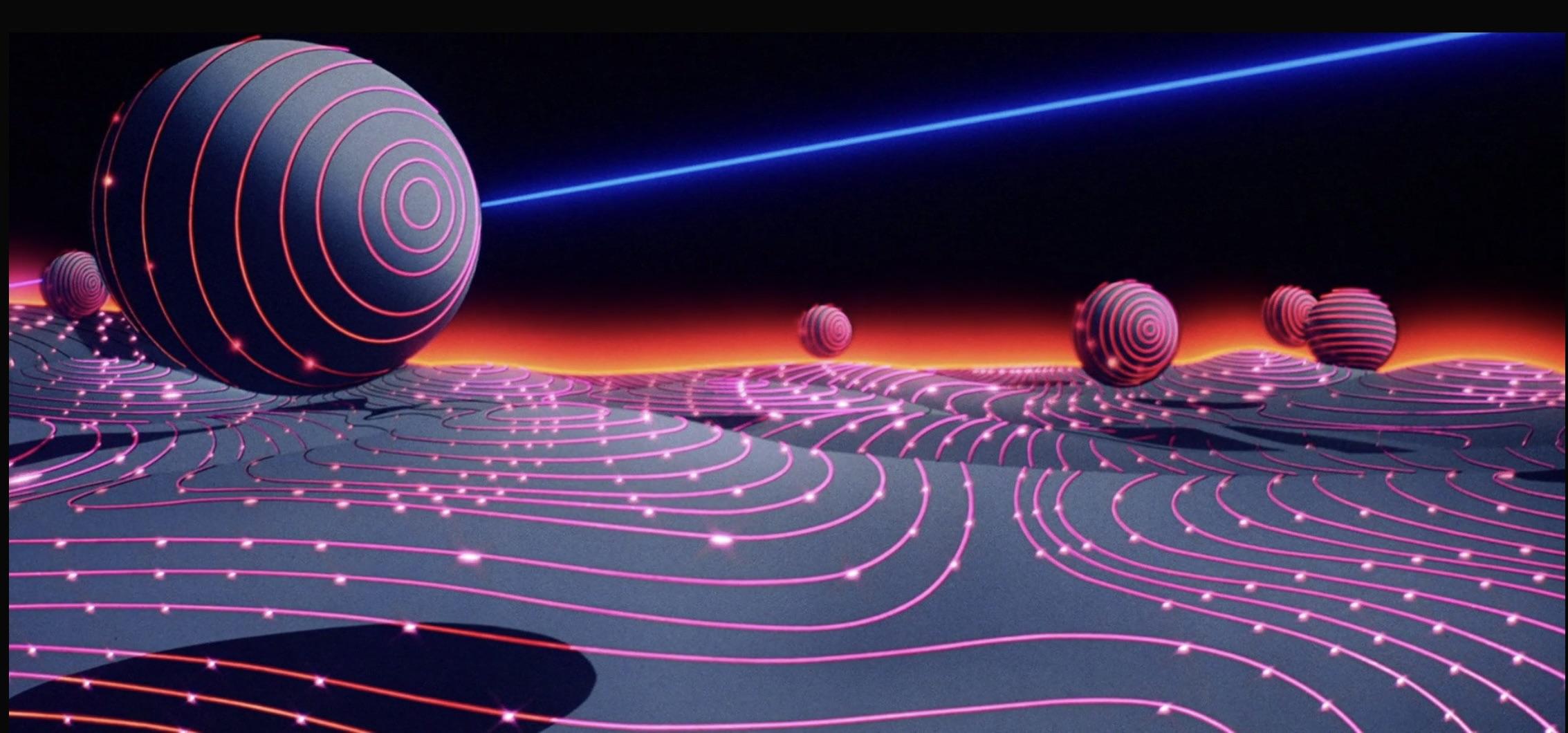

The original Tron is a fantasy movie. I know it carries the trappings of science fiction, and if we’re being technical it fits, but it’s very much on the fantasy side of fantasy / sci-fi. This movie cares about as much about computers as The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe cares about European medieval government. The Grid has nothing in common with computers.

No… In terms of genre, the original Tron is an Alice in Wonderland story. The world inside the computer—“The Grid”—is a fantasy land that serves as a setting for our hero to wander through. Yes, he has an ostensible mission and yes, at the end, he accomplishes his goals, but he does so very abstractly relative to the actions he undertakes. In essence, there is a story already happening in this world and he is mostly a visitor; his visit has impact, he ends a monarchy, but it isn’t even clear to him while undertaking those actions that his goals will be served by them.

Indeed, there is a character in this story with clear goals, a clear enemy, and a clear victory. He’s easy to identify because his name’s in the title.

And in all the promo images, and he has a convenient T on his chest

While Kevin Flynn takes heroic actions and is a hero, the story that happens in the Grid is Tron’s story. Tron has a reason to defeat the Master Control Program. Tron lives in the world; Flynn is just a visitor.

The thin veil

There are two things this movie sets up that are relevant to the future, of Tron and of our real world.

The first is a short conversation Flynn has with Tron and Yori, after Tron learns that Flynn is one of the fabled “Users,” the minds on the other side of IO ports that created the world and guide the programs with their commands.

Tron: If you are a User… Then everything you’ve done has been according to a plan, right?

Flynn: laughs You wish. You guys know what it’s like… You just keep doing what it looks like you’re supposed to be doing, no matter how crazy it seems.

Tron: That’s the way it is for programs, yes.

Flynn: I hate to disappoint you pal but most of the time that’s the way it is for Users, too.

The second is the last scene of the film, the exiting shot right before the credits. Flynn has taken over the company and greets his colleagues with a hearty “Greetings, programs!” And the film closes on a sped-up image of the Los Angeles city grid, as the sun sets, leaving the city traced in the lights of office windows and cars in the street.

That’s the way it is for Users, too

The problem with every Tron sequel

The problem with every Tron sequel is that you can’t remake Tron.

This isn’t a technical challenge issue; it’s an era issue. Tron is from an era where computers were magic. You could tell any story you wanted to about their goings-on because people didn’t understand them. They did very few things (but very quickly when they did them), but they oozed potential. It didn’t take much imagination to extrapolate into the possible with them, and Tron hit at a time when the possible was just beginning to glimmer on the horizon.

Remaking Tron isn’t a problem of vision, budget, or creativity. You can’t remake Tron because we aren’t there anymore. We carry computers in our pockets approximately 2,000 times the computing power of the machines Disney contracted in the ’80s. You are likely reading this on a machine powerful enough to render every CG effect in the original Tron in about one minute. The kind of effects Disney spent $1.2 million in compute and engineer time on are now used to sell car insurance.

… and now you hear the jingle in your head.

It’s hard to make a fantasy story atop the utterly mundane. Alice in Leeds is just not as exciting a tale.

Possibly worth noting is that I haven’t really touched on the plot of Tron. As with Alice’s tale, it’s because the plot isn’t deeply relevant to the point-of-view character’s story; things are just sort of happening. Tron’s plot is about a central computer “enslaving” programs to its core operation, gaining more and more power as it does so and growing to a point it risks being uncontrollable by Dillinger, its owner. In an interview with The Guardian in 2022, Tron screenwriter and director Steven Lisberger stated one theme of the movie was the power asymmetry between governments and corporations using computers and the people who were indexed into the data in those computers. “I’m already in your system. So why is it I don’t have access to myself?… It was a story of rebellion and revolution, and founding a new frontier that would enable a new civilisation to take hold.”

In that regard, I think Tron had a sweeping effect. Although the fight between a “Master Control Program” and separate programs serving seperate users has little reflection of modern computing (every one of us is running a Master Control Program; we call those “operating systems”), the human themes of “Who does this system serve?” and “Consolidation and systemization vs. freedom” resonate. Hackers, to the extent they represent a culture, did and continue to style themselves in a punk, DIY aesthetic that bucks authority and challenges people to ask questions like “What does this system do,” “What happens when this breaks,” “What can we make in this, our own private world,” and “Who has the real power here.”

Tron fought for the users.

Tron: Legacy is telling the right story the wrong way

So fast forward to the 2000s and someone at Disney has the brilliant idea to pull Tron out of the fridge, dust the frost off, and make a sequel.

Tron: Legacy is… Not a bad movie. It’s shiny. There’s a good movie in there. The problem with it is that it’s got a compelling plot but it tries to present that plot with the trappings of the first Tron and… It just doesn’t quite work.

Let me tell you a story that has very little to do with computers.

Once upon a time, there was a man obsessed with the power of creation. He gained glimpses of the possibility of a world science could create. In his obsession, he threw himself into his work, neglecting family and friendship to pursue his singular vision. And, against all odds, he succeeds. But in his monomaniacal pursuit, he’d failed to pay enough consideration to what the consequences of that success would be. Utterly unprepared to face those consequences, his family suffers greatly and he is utimately unmade by them.

The man’s name, of course, was Frankenstein.

His creation was too delicious for this world.

Tron: Legacy is a Frankenstein story at its core. CLU is Flynn’s monster: a program he builds intending to create the perfect system that he loses control of. There are some twists thrown in: he loses that control because the genesis of the ISOs distracts him from managing and shepherding CLU. Not unlike Mary Shelley’s monster, CLU is not inherently evil; he was given insufficient direction and too much power, a child with a gun.

This thread is pulled taut at the end of the story when CLU confronts Flynn, Sam, and Quorra on the access bridge to exit The Grid. After a tense confrontation between CLU and Flynn, where Flynn admits CLU was given an impossible task because when he was created, Flynn himself did not know the task was impossible, Flynn ultimately betrays CLU and sacrifices himself to allow Sam and Quorra to escape. His response to CLU’s simple, plaintive “Why?”

“He’s my son.”

Tron: Legacy is a good Frankenstein story.

It’s a shame it’s told like an Alice story and, despite the excellent work the effects and audio teams did… Wonderland just doesn’t measure up.

The holes, rabbit-filled and otherwise

The original Tron recognized that while its point-of-view character was important to the story, the story was about someone else. Tron: Legacy doesn’t seem to grasp that. For the story being ultimately Flynn’s story, we simply spend too much time with Sam. His quest to find his father is key to instigating the plot, but he’s then thrown from scene to scene (not unlike the first movie) until encountering Flynn and at that point… He’s superfluous. Flynn is already a good point-of-view character. Quorra is already the adopted child in the tale, contrasting Flynn’s intentional creation of CLU with the messy, unexpected creation life throws at you. Everyone has a role except Sam.

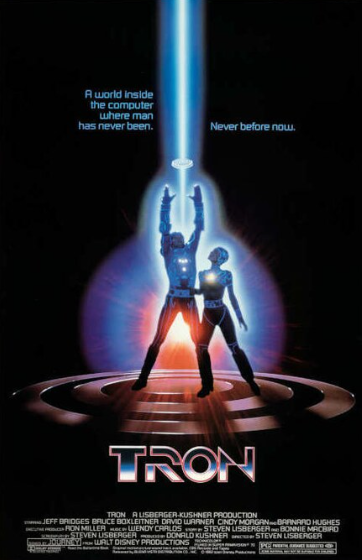

Notice Sam is standing where Tron is in the original movie’s poster, suggesting he should be main character. The story seems to think he matters most.

To be fair, Sam has growth in the tale and he goes on a hero’s journey, like Flynn did in the first movie. But like Flynn in the first movie, most of his job is to bear witness: he enters the Grid intentionally to find answers, and his reward is he finds them. But in this tale, Flynn has set up the antagonist, Flynn has something to prove, Flynn saves the day, and the final showdown with CLU is about Flynn’s growth, not Sam’s. The movie does a bad job of holding together as a result, and the ending feels a little flat.

Tron is also here.

One of the challenges of the computer world being less magical this time around is that as an audience member, I’m left analyzing the actual plan of the villain, and it’s stupid. CLU wants to fly a whole aircraft carrier into the real world. We, the audience, have no reason to believe that would work, so the stakes are a bit flaccid; they put a rule on the IO port about it being timed, but apart from that there’s no good reason to race CLU to the port, because if he gets there first, he’ll try to ship his army through, the carrier will spaghettify against the wall because it’s too big to fit in Flynn’s office, and our heroes can just waltz through the portal afterwards, stepping around the carrier debris and squashed programs on their way out.

Three tweaks I would make to this script to make the stakes work better:

-

Either remove the scene where Sam gets cut in the Grid or show the cut is pixelated, maybe a little scar he carries until Flynn can repair him. Draw a thicker line in the sand between the Grid world and the real world: Users are still special when digitized, but their biology is digital like everything else.

-

Have Flynn know CLU’s plan definitely will not work. “A program can’t live in our world. You think that wasn’t the first thing I tried? Instantiating Tron so he could shake the Board’s hand? No. He lasted eight seconds in our world and I had to restore him to the Grid from backup. Programs just can’t exist out there; they’re not the right kind of stuff."

Instead, CLU has to be stopped because he definitely can’t exit the Grid, but if he tries, he’ll brown out the power the laser is drawing from, shut down the computer, and kill everyone in the Grid. -

Have Flynn not know if Quorra can exit the Grid, but have it be the plan. “Can she leave? Maybe. I don’t know. ISOs aren’t regular programs. But Sam… I can’t hide her forever. If she stays here, she’ll die.” This gives deeper stakes to Quorra’s arc and makes it a big reveal that she’s there in the end scene. This also ties some plot holes up nicely, like “Why did Flynn never extract Tron or any other program or ISO from the Grid in all the time he was working on the project?”

What did work, what pays forward

While I think Tron: Legacy had some holes, I think there are some bits that work well, reflect on the past, and pay forward.

-

CLU mirrors the MCP in an excellent way. He wasn’t necessarily created to be one, but his arc suggests that the very goal of perfecting the system leads to a fascist architecture. This creates a system where a miracle of digital abiogenesis happens and the system ultimately stamps it out as an irregularity.

-

Contrasting this, the older, wiser Kevin Flynn has found a Zen acceptance of ultimate lack of control. He has learned to de-center himself from the equation, a philosophy that lets him survive his years of isolation. And, ultimately, he wins the day by recognizing the moment his own sacrifice would guarantee victory for those he cared about and seizing it. This theme, victory through the exhaltation of another, is echoed in the original movie (Flynn jumps into the MCP to disrupt it not because he thinks it’ll win his goal, but because he wants Tron to win his) and pays forward into the next one.

-

Tech CEOs can make incredibly boneheaded mistakes. This will be relevant in the future.

I should probably note that in addition, a wise acquaintance has noted:

“Tron: Legacy has Michael Sheen playing David Bowie meets the Merrovingian jacking off lasers into a crowded room. I think that by default makes it the greatest movie of all time.”

I cannot argue with that logic.

An interlude: Tron 2.0 and a webcomic

Two brief observations.

Number one: in 2003, the game Tron 2.0 was published, which tells the tale of a son of Tron’s programmer, one Jet Bradley, being digitized into a new Grid to combat the technology’s use as a military tool. A McGuffin here is the “correction algorithms,” a necessary ingredient to being reconstituted in the real world that was lost when the Master Control Program was destroyed. Without the algorithms, people digitized into the Grid come in “corrupted” and cannot be reconstituted. This feels like a precursor to the “permanence code” in Tron: Ares.

When you forget to carry the two.

Number two: comic artist Stephen Notley, creator of Bob the Angry Flower, did a comic after the release of Tron: Legacy giving the things he’d hoped to see in a Tron sequel. See how many have echoes in Tron: Ares. I suspect this is coincidence.

Tron: Ares is a better Tron: Legacy

So anyway, Tron: Ares is a better movie because…

… oh wait, sorry, I have to go Light Cycles a guy real quick. I forgot I’m still banished for the heresy.

But, gentle reader, here’s my case. Ares is a better Frankenstein story. It stops holdling the trappings of a Wonderland tale and embraces its monster, and in doing so, gives us another twist on Mary Shelly’s tale.

Someone’s a ‘Bob the Angry Flower’ fan.

We get a quick pick-up during the opening credits: Sam and Quorra disappeared after Tron: Legacy but the digitization technology somehow resurfaced, or was independently discovered, or never really went away? Dillinger’s grandson now heads a company with his family name, and they and ENCOM are in a race to make the tech workable. The missing McGuffin: a “permanence code” that allows digitally-originated constructs to stay permanently constituted in our world. Without it, things “printed” by the lasers derezz after 29 minutes. But apart from that, the laser tech blurs the lines between the digital world and our own: digital-originated constructs seem to run on fantastical energy sources and behave in a quite otherworldly fashion in our reality… But they work. Dillinger and his company want to make soldiers and tanks permanent; ENCOM, headed by new CEO Eve Kim in Sam Flynn’s absence, seeks to create fruit tree groves.

But that’s all backdrop.

Ares focuses on the charcter undergoing the most growth: the monster. The titular Ares is one of Dillinger’s soldiers, exhaustively trained in combat via reenforcement learning (represented by a “Live-die-live-again” montage in the beginning of the movie, and a surprisingly good analogy for how actual reenforcement learning works in neural nets) and granted “Master Control” rank across the Dillinger corporate grid. He is functionally immortal, his experiences uplinked to train his neural net continuously and a backup always ready for restoration.

He’s rezzed for 29 minutes into the real world as a demo and his experience of the real world quite destabilizes his dedication to his directives. The plot then centers on his arc: betraying Dillinger, seeking the permanence code for his own selfish reasons, but ultimately meeting an “echo” of Flynn in a backup of the original ENCOM Grid and convincing Flynn that despite his origins, he understands enough about life to be worthy of living it (although Flynn warns him: living like a human, you only get one shot… He jokingly calls it the “impermanence code”). In the end, he acquires the code so he can re-enter the world to save Eve Kim from Athena, a second Dillinger soldier-program promoted to “Master Control” after Ares goes AWOL. Athena pursues her directives with monomaniacal fervor, killing Dillinger’s mother in the process. In the end, Dillinger, disgraced and devastated, banishes himself into his now-destroyed Dillinger Grid and Ares, in the end, escapes to seek out where Sam and Quorra may have gone.

Ares is messier than the two previous movies. The themes are trickier. The Grid serves as more of a backdrop: it’s beautiful, but it doesn’t need to be Wonderland. Instead, its painted as a place that horrors can emerge from. Perhaps reflecting modern experience with technology, it is not a utopia, and the things projected by it into this world are dangerous; unchecked, they can move fast and break things. Ares does not fight for the Users because the Users can’t agree on what you should fight for (and, indeed, where they’re treated as objects of worship or at least respect in the first two films, Users in Tron: Ares are seen as peers once the programs can be incarnated in our world). Ares’s plot arc is a bit of a subversion of the original Frankenstein story: in the original (and, arguably, in Legacy), it is through neglect of his creation that Frankenstein comes to ruin. In Ares, Dillinger pays meticulous attention to his works, but to only one monomaniacal end with no room for other possibilities. When Ares learns empathy and compassion from his interactions with other humans, he can’t be solely the instrument of action he is intended to be and grows beyond Dillinger’s control. Athena, in contrast, highlights the danger of too much control towards an ill-planned goal; she follows her directive with no deviation, and in so doing kills her creator’s mother, forces the loss of her home, and ultimately dies a final death in our world, her clock expired and no backup to be restored.

Tron is also not here.

Ultimately, Tron: Ares tells a good tale of pursuing the wrong ends, growing beyond one’s limitations, and the common thread across all three movies: the ultimately messy nature of the human quest to put order into our lives, to build something lasting, meaningful, or “perfect.”

The future of Tron

Will there be another Tron movie?

As a huge fan of the original: I don’t need there to be one. There’s multiple reasons: it’s a series called Tron with no need for Tron, and the technological status quo at the end of this movie is teetering on the brink of singularity: Sam and Quorra had to disappear because “life from computers” would have been the kind of world-breaking discovery that would have made the setting for Tron 3 unrecognizable, and at the end of the movie we did get there’s a company that can make infinite fruit trees (and, technically, infinite weapons if they want, or laborers for those fruit farms that never tire but might start asking pointed questions about their purpose and having opinions on Depeche Mode). There might be room for an interesting Tron TV series exploring these themes of where this technology leads, but… Wonderland isn’t wondrous anymore, and that sort of undercuts the premise.

Some stories aren’t timeless. I’m glad Tron exists. It’s a product of a specfiic era where we were at the top of a roller coaster that was about to plunge us all into a permanently-digital era, an era that blurred the digital and physical world in the most mundane way possible.

But oh, to be a kid in the ’80s imagining what that world would look like.

Comments